Nazi Germany, was, in every sense, a totalitarian dictatorship. Through the whims of just a few powerful men, it caused and facilitated more destruction than perhaps any other state or institution that has ever existed in the history of the world. With absolute power in their hands, Adolf Hitler and his inner circle had complete control over anything that happened within Germany or the territories it later controlled. Any internal opposition to the ideas or actions of the Nazi Party or its leadership would quickly be snuffed out by cruel agencies such as the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police. The Nazi regime is rightfully remembered as the historical epitome tyranny and oppression; the antithesis of liberty and democracy. It is therefore surprising to learn that Hitler and his inner circle first came to power largely by legitimate means. That is, they were elected through free and fair elections or appointed by existing government officials as allowed by the constitution of the Weimar Republic. While Hitler eventually transformed Germany into the despotic nightmare that the world has come to despise, his unassuming rise to power reveals one important fact about the Nazi party: that the ideology that the party produced was not merely the insane machinations of a few corrupt politicians, but a complete set of social, moral, and political ideas that genuinely captured the hearts and minds of the German people.

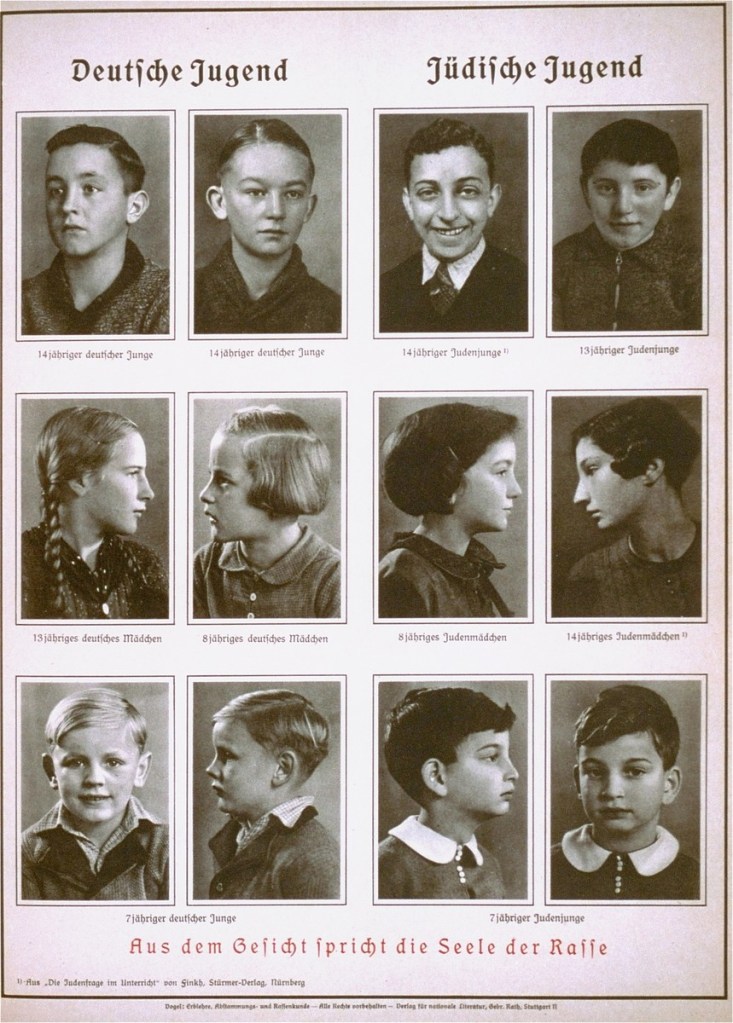

Though there were a number of factors that allowed for the rise of the Nazis, one issue on the minds of many Germans was the standing of the German people in relation to the rest of the world. The humiliating result of the First World War and the economic hardship as result of the worldwide Great Depression left Germany in a weaker state than it had been in for decades. Therefore, the Nazis capitalized on the people’s desire for German strength, empowerment, and respect. This led to the creation of the myth of the Herrenrasse, the superior race of humans. This and other myths central to the Nazi party’s ideology were themselves derived from much older myths originating from the Nordic and Germanic cultures that predated the Nazis by centuries. Like the Yoruba myths in West Africa, these myths were modified or outright rewritten to further the political agenda of the Nazi party. More specifically, it upheld the notion that the peoples of Central and Northern Europe were inherently superior, and therefore justified the continued aggression of Nazi Germany, by claiming and maintaining Germany as the world’s dominant people.

Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Goebbels—all names typically associated as being the core of the Nazi party. But one name often less remembered by popular history belonged to man whom Hitler himself credited as being a spiritual co-founder to Nazism: Dietrich Eckart. Eckart was a political writer and poet from the Bavaria region of southern Germany, who was active in the earliest days of the Nazi party, helping create the underlying principles of the Nazi party, as well as the personality cult surrounding Adolf Hitler. A fervent anti-Semite, many of Eckart’s works featured furious ramblings about the growing influence of Jews in Europe, and the responsibility they held for the decline of Germany. He considered Jews as an outside, corrupting force that was weakening the German people, and saw Hitler as a messiah who would save them. However, there was a key problem in convincing the German people in Eckart’s vision. Germany, for most of its history, was not unified under one political or cultural entity. Eckart himself was born in the Kingdom of Bavaria, which was effectively its own country before it became a part of Germany. How could the German people unite against their Jewish enemy if they could hardly find unity among themselves? The key was through finding a common heritage in Nordic and Germanic folklore.

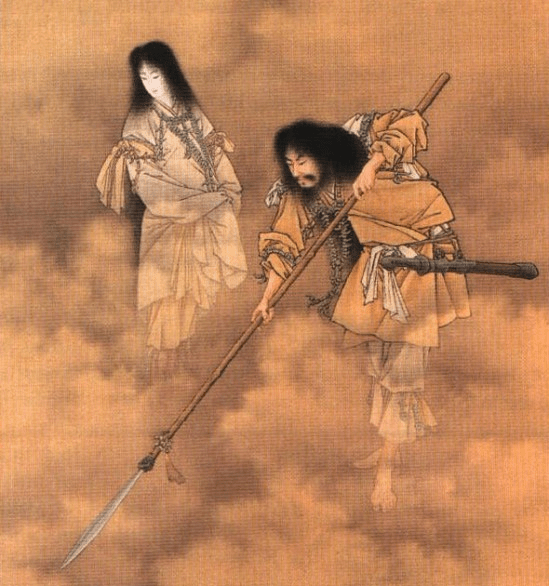

Eckart, alongside future prominent Nazi officials such as chief Nazi racial theorist Alfred Rosenburg, belonged to a occultist organization in Munich called the Thule Society, named after a legendary Northern European nation that appeared in Roman and Greek mythology. The society believed in a perfect, almost superhuman Aryan Teutonic race. They believed this race descended from the mythical land of Atlantis, and later migrated into Germany where they became the Germanic peoples we know today. The society claimed, however, that the race was in danger, and was being corrupted by races inferior to them, such as the Jews. Not did they believe that a cultural and genetic destruction of the master race was taking place, but also believed that it was actually part of a deliberate plot by the enemies of the Aryans to take power and remove the Aryans from their rightful place at the apex of human civilization. In the end it was actually the Thule Society that first sponsored the German Worker’s Party, which, under the direction of Hitler and his henchmen, would transform itself into the Nazi Party.

While the Nazi Party did adopt its own original mythology through Nazi-affiliated scholars such as Eckart or Rosenburg, it did incorporate elements of existing European mythology to strengthen its connection to its alleged Aryan heritage.

One example of a Nazi attempt to directly tie itself to Northern European tradition can be seen in the emblem of SS, the Nazi paramilitary group that was under the direct control of the Nazi Party. The emblem contains two Germanic sig runes, which both mean “victory”. The SS emblem is now one of the most enduring symbols of Nazi Germany.

Today, mythology, whether from ancient European traditions or Nazi racial theory, continue to be part of the far-right movements of the present. Symbols such as the Celtic Cross and Triskele are used by certain white supremacist groups, which, by using these symbols, attempt to call back to a sense of common European heritage and pride. As tragic as it is, there can be no denying that the traditions and symbols of several Northern and Central European cultures has forever been associated with the actions of a few individuals. The complex tale of the development of Nazi ideology provides a sobering tale for what it means to embrace or butcher the truth, and how easily the line between the two can be blurred.