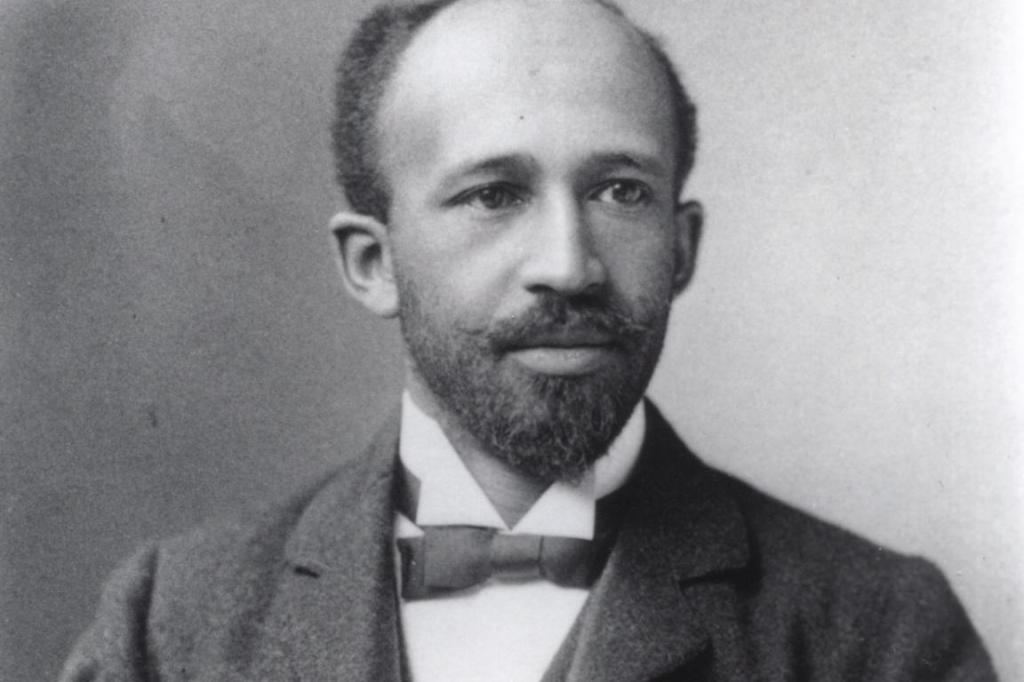

The era of “Jim Crow”, a period of American history with widespread societal and legal discrimination against African-Americans (especially in the South), is generally considered to have ended with the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Famous leaders from this period, such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and others are widely celebrated, since their actions took place at the climax of the movement. Less appreciated, however, are the many leaders who paved the way for this celebrated generation of activists, many of whom, including the subject of today’s article, never lived to see the fruits of their labor.

Charles Hamilton Houston was born in 1895 to middle-class African-American family in Washington D.C. Houston’s father, William, was an attorney. Houston was described as a brilliant child, graduating from Dunbar High School at the age of 15. He then went on to Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he left as one of six valedictorians in his class. Following a brief stint teaching English at Howard University, Houston applied as an officer to the United States Army upon the country’s entry into World War I. This was a formative experience for the young Houston, who witnessed the constant bigotry and racism that was present in a still segregated army. Using the law, he was determined to right the wrongs he saw everywhere. Houston returned to the United States in 1919, shortly after the war’s end. He enrolled in Harvard Law School, becoming the first African-American to serve as an editor of the Harvard Law Review, and graduated with honors in 1923. Houston was soon admitted law to District of Columbia Bar, where he would begin to practice law alongside his father. He also aided in the creation of the National Bar Association, which unlike the dominant American Bar Association, recognized and accredited African-American attorneys.

Beginning in 1924, Houston returned to Howard University, only this time teaching law instead of English. Mordecai Johnson, the university’s president, saw potential and Houston, and allowed him a significant role in reforming Howard Law School. Although it was responsible for training three fourths of the country’s Black lawyers, Howard Law School still only held part-time night classes. After Houston was appointed vice-dean (effectively with the powers of a dean) of the law school in 1929, he helped bring about its transition into a full-time law school. With his new role as the head of the African-American law’s central institution, Houston envisioned a new generation of Black lawyers who could use their skills for the advancement of their people. Among his students were James Nabrit, Oliver Hill, Spottswood Robinson, and Thurgood Marshall. Houston’s role in fighting Jim Crow, however, was not limited to the classrooms of Howard University. Rather, by working with the attorneys he trained himself at Howard, Houston was able to make considerable strides towards racial equality under the law.

Resigning from his post at Howard in 1935, Houston would spend the remainder of his life working on civil rights law. He assumed the position as the first special council to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). One of his first cases following his departure from Howard was in Hollins v. State of Oklahoma, which concerned a Black man sentenced to death by an all white jury. Houston and his all-black defense team were able to prevent the man from being executed. Though it was a goal of Houston to rid American juries, it would be decades before that become a reality. Another of Houston’s primary concerns was the segregation of public schools, which was deemed constitutional by the 1897 Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, under the doctrine of “separate but equal”. He would dedicate much of his work towards attacking this doctrine, which he believed was the keystone for much of Jim Crow’s stranglehold on the South. Alongside Thurgood Marshall and the Baltimore branch of the NAACP, Houston argued in Murray v. Pearson before the Maryland Court of Appeals. The case concerned Donald Gaines Murray, an applicant to the University of Maryland School of Law who was rejected due to his race. The court ruled in Murray’s favor, and ordered the school to admit Murray. This ruling, however, did not mean the end of segregation in America’s, or even in Maryland’s schools. The court noted that only because the University of Maryland School of Law was the only law school in the state, did the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment apply. In theory, a separate Black-only law school could legally exist in Maryland. Nonetheless, this was heralded as a victory for Houston and his devoted followers.

The precedent of outlawing segregation in institutions which were the only of its kind within its state was carried on to the federal level, thanks to Houston’s work in Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada. This case was very similar in background to Murray, with the added impact that it started to raise doubt within the Supreme Court of the United States about the legitimacy of “separate but equal”. Still, however, the doctrine remained as the official legal precedent in American law. Concurrent with his struggle towards desegregating American schools was Houston’s battle towards racist housing covenants. These were legally binding contracts attached to properties that restricted who could purchase it, which often meant discrimination against prospective Black homeowners. Using these covenants, real estate developers could directly control the demographics of the neighborhoods they built. In 1948 the Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kramer that the enforcement of these covenants by state or local authorities was unconstitutional, thus ending a decades-long battle by Houston and the NAACP. Though Houston himself did not argue before the court, his advice and connections to the Howard Law School alumni who did, are another example of Houston’s vital role in dismantling Jim Crow on multiple fronts.

Charles Hamilton Houston died of a heart attack on April 22, 1950, at the age of 54. Just four years after his death came the landmark decision Brown v. Board of Education, which successfully overruled the doctrine of “separate but equal”. The case was headed by the director-counsel of the newly established NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and one of Houston’s most loyal disciples, Thurgood Marshall. In 1967, Marshall would be appointed by Lyndon B. Johnson as the first African-American justice to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States.

We owe it all to Charlie.

– Thurgood Marshall