What do decorated college and professional basketball player Wilt Chamberlain and a storied group of anti-slavery militias have in common? Both of their titles: “Jayhawk(er)”, are deeply connected to the history of Kansas. The term has been used to represent the University of Kansas and its athletics teams, but also for Kansans as a whole, and has become a symbol of pride for the entire state. Contrary to its name and cartoon image, the Jayhawk is not actually a real bird, and while the name is one recognized across the United States, few outside of the state of Kansas may know the term’s true, and rich history.

The term “jayhawker” is most likely a compound word between the blue jay and sparrow hawk. It was first coined by the original Kansas settlers who admired both the blue jay’s turbulent personality and the sparrow hawk’s predatory nature, and the term became applicable to anyone from the region. It was not long, however, that the story of Kansas took an sharp turn, as the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1954 was signed into law. The bill, passed during a time of divisiveness over the issue of slavery, granted the newly formed territories of Kansas and Nebraska to right to decide by referendum whether they would be open or closed to slavery. While intended as a lasting compromise between pro and anti-slavery factions in the US, it only heightened tensions over the issue, which would lead to—preluding, of course, the American Civil War—a period known as Bleeding Kansas.

As word spread about the policy through which Kansas and Nebraska would decide their stance on slavery, thousands of armed supporters on both sides flooded west hoping to skew the favor in one direction or another. The southerners, hailing mostly from neighboring Missouri, were motivated by a staunch opposition to that they viewed as tyrannical abolitionism. The majority of northerners, on the other hand, were only somewhat abolitionist, most feeling little sympathy for enslaved Africans. These settlers were mostly part of the Free Soil movement, primarily concerned with protecting the White American family farm, which would no doubt be endangered by the expansion of southern-style plantations. In fact, the majority of supporters from this movement supported outlawing Blacks, free or enslaved, from entering the Kansas territory at all. Only a small portion of northern settlers, such as the legendary John Brown, were opposed to slavery on mainly on moral grounds. As the two (or perhaps three) sides, both armed and ready to fight, began to enter their area, an interesting assortment of nicknames began to sprout for different groups during the late 1850s. The pro-slavery bands during Bleeding Kansas were generally called “bushwhackers” due to their ambush tactics and criminal reputations, while similarly aligned groups that specifically came from Missouri were called “border ruffians”. Finally, their abolitionist counterparts, seeing themselves as rightful defenders of Kansas from pro-slavery aggression, adopted the name affiliated with the region itself: “jayhawker”.

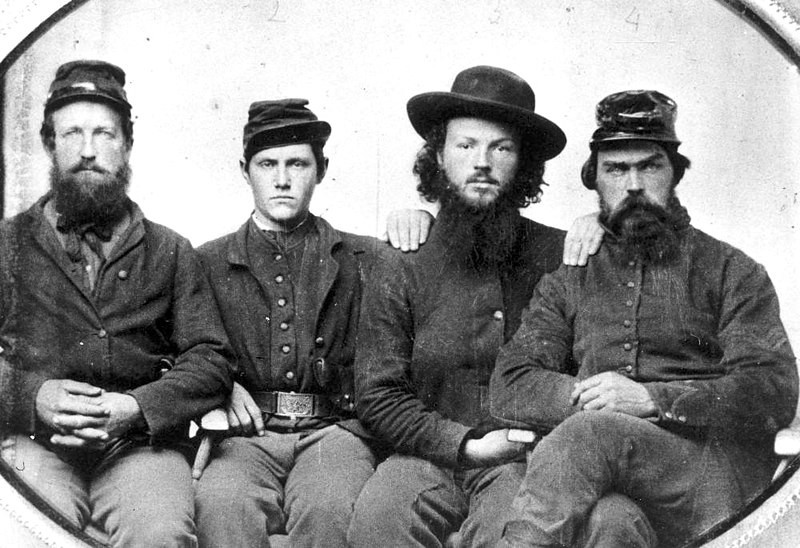

Charles Rainsford Dennison, famed jayhawker and perhaps the most fashionable officer of the American Civil War (Dickinson College)

While the dubious motives of the anti-slavery faction may very well on its own do enough to disprove the notion of Bleeding Kansas as a noble struggle between good and evil, it is the means through which both sides carried out their beliefs that is perhaps what made the conflict so ugly. Jayhawkers were known to use any means necessary to combat their enemies, not hesitating to murder or pillage to further their cause, but also to earn personal land and monetary gains from those they murdered or pillaged. As the intra-Kansas conflict continued into the much larger Civil War in 1861, so too did many of the jayhawkers’ and bushwhackers’ tactics. Union and Confederate leadership alike detested the work of those such Charles Dennison, a notable jayhawker who led a Union militia cavalry unit notorious for its brutality and willingness to use extrajudicial killings. A more respected, although equally uncompromising fighting force that adopted the jayhawker moniker was Lane’s Brigade, under Senator and Brigadier General Thomas H. Lane, which earned many victories along the Missouri border. Throughout the war much of the Western frontier conflict was defined by unhinged guerilla warfare, as thousands of civilians were robbed, displaced, or summarily executed by militants on either side of the conflict, as seen in the Lawrence and Osceola raids.

As the guerilla conflict cooled off and the Civil War came to a close, the name “jayhawker” remained in the hearts of Kansans, who did not see the term in the same negative light which their former enemies had, but instead embraced it as an homage to Kansan statehood and its contributions to the Union cause. In 1890, just 25 years after the end of the war, the University of Kansas football team took the field for the first time, proudly calling themselves the Kansas Jayhawkers. Today, the KU athletics teams instead use the truncated name “Jayhawk”, which despite its far-from-perfect origin, continues to be the symbol of Kansan pride it was 150 years ago.