Walk far enough along Canal Street through the heart of Lower Manhattan’s Chinatown, and you will eventually find a notable street marked with two different names: Elizabeth Street and Private Danny Chen Way. A quick Google search will reveal the tragic story of the road’s secondary namesake. Private Danny Chen died by suicide in Afghanistan after receiving intense racial abuse at the hands of his fellow soldiers. Chen, hailing from the very same neighborhood, was honored by his Chinatown community shortly after his untimely death. While the practice of naming landmarks after fallen soldiers is by no means unique, neither is Chen’s story of facing racism within the ranks of the United States military. Since Washington’s initial refusal to enlist Black soldiers in his Continental Army, racism in the American armed forces have been a notable subtopic within the larger study of American race relations. Though significant progress has been made since the country’s first battles, recent incidents such as the suicide of Danny Chen have drawn concern to the status of racial minorities in the military, as well as how incidents of racial abuse should be addressed, especially when the abusers have direct authority of the victim.

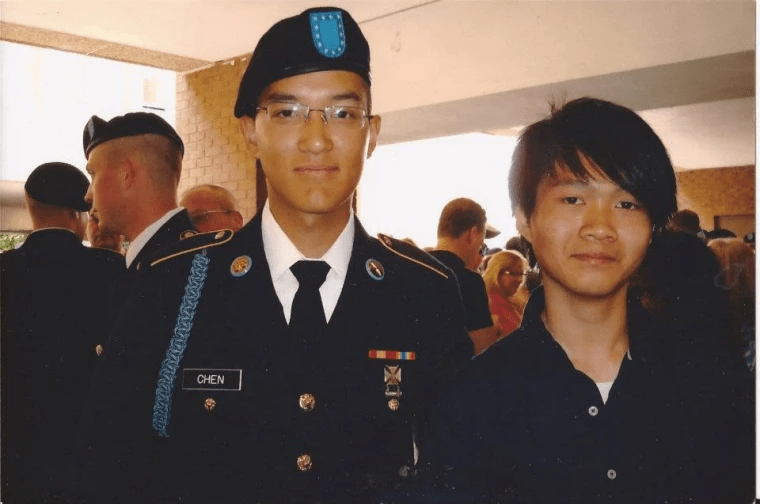

Born in 1992 in the largest overseas community of ethnic Chinese in the world, Danny Chen grew up similar to many of his peers. His mother was a seamstress and his father was chef, both of whom immigrated from Taishan, China. Chen was the tallest in his family, standing over six feet tall. He was bright, social, and devoted to his family. He worked hard both in and out of school, and was considering attending Baruch College, from which he received a full scholarship offer. However, as his high school days came to a close, his interests shifted, considering a career in the military instead. He planned to enlist in the Army, and dreamed of later becoming an officer for the NYPD. His family, on the other hand, were not so enthusiastic about his new goals. Him being his parents’ only son and child, they hoped he would pursue a safer career by getting his college education, believing that he had a bright future. In the end, however, Chen chose to pursue his dream of serving his country and community, and enlisted in the military shortly after graduating high school.

Chen first reported for basic training in Fort Benning, Georgia, where he got his first taste of military life. Like many new recruits, Chen was eager for the weeks ahead. He wrote to his parents often, describing to them how toilet paper was particularly rare on base, or how intrigued he was when shot a gun for the first time. But as time went on, and the stress among his fellow recruits mounted, his attention was increasingly called to a peculiar fact: he was the only Chinese man in his platoon. Week after week, recruits would call him “chink”, “Ling Ling”, and a variety of other racial insults. While the words themselves did not bother him, it become more and more apparent that he was being singled out within his platoon due to his race. At the time of him joining, Asians-Americans of any background made up just four percent of the entire US military. This fact, in addition to being the first in his family to join the military, made it so Chen had no one to turn to, and had to handle the situation without anyone truly on his side. Chen was a rather shy and unassuming figure, and tried to deflect the verbal abuse as best he could with humor. In the end, Chen was able to survive basic training, and in April 2011, he was assigned to the 21st Infantry Regiment of the 25th Infantry Division, based in Fort Wainwright, Alaska.

While his status as the only Chinese in his platoon did not change, he tried to make the most out his situation in Alaska. After his expected deployment to Afghanistan was delayed, Chen spent his time with friends in and around base, hoping to overcome that barrier which seemed to always divide him and his fellow soldiers. But in August 2011, after months of impatiently waiting, he and his unit were finally deployed into Kandahar Province, Afghanistan. As eager as Chen was to serve his country and prove his worth, the racial abuse, coupled with extreme hazing, only become worse. He was berated constantly with racial slurs, and was even forced into communicating orders to his comrades in Taishanese, the Chinese dialect of his parents. He was frequently singled out for extra guard duty, to the point where he would fall asleep on the job, and would be brutally beaten by his fellow soldiers as punishment. In one incident, Chen was dragged naked across 50 feet of gravel after misusing a water heater. Chen’s final day of service would be similarly humiliating. On October 3, 2011, he forgot his helmet for guard duty, leading to him be pelted by his platoon with rocks as he forced to crawl back to his trailer to retrieve it. Other soldiers observed that Chen seemed hardly phased by the ordeal, until the truth revealed itself later than morning, when Chen, age 19, was found dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head.

Of the eight men charged with Chen’s death, they officially served a total of 11 month in prison. The majority of the accused, including the lieutenant who commanded the platoon, had their charges dropped, or received no sentence and were instead demoted or discharged.

Chen’s death was not the first of its kind. Hazing in the military, especially against soldiers belonging to racial and ethnic minorities, as long been of concern. Around the same time Chen completed basic training, a Chinese-American marine named Harry Lew committed suicide in Helmand Province, Afghanistan after being beaten and having sand thrown in his face by a superior. Five years after Chen’s death, Pakistani-American marine recruit Raheel Siddiqui jumped off of a bridge after receiving abuse at the hands of a drill instructor with an established history of mistreating Muslim-American soldiers.

As racial discrimination reports continue to be received from concerned soldiers, many are troubled about how the culture of the military should adapt to an ever increasing diversity in the among its ranks. While history has shown the ugly side of American race relations across many of its institutions, it appears that within the United States Armed Forces, the concerns of the past continue to be felt in the present.