Throughout history, mankind has always sought the truth. Education allows humans to pass on the truths we discover onto the next generation. As discussed in last week’s article, education is one of a civilization’s most important tools for shaping itself, as the central principles that guide any people are the ones passed on through learning. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, first published in his 1859 book, On the Origin of Species, became far more than a scientific breakthrough, soon becoming a catalyst for larger debates about the relationship between science and religion.

Though the United States was one of the first modern societies to founded with an adherence to the idea of the separation between church and state, its ties to Christianity were inevitable due to an overwhelmingly large proportion of its population being Christian. As a result, Bible-oriented, theistic sciences were almost universally taught in American schools, though this fact can also be attributed to there being few other contemporary explanations for the natural world. With regards to the origins of humans and the natural world, things were explained through an ideology known as creationism: that both humans and nature were created by a divine, intelligent deity. This deity, of course, fit neatly into the description of the Abrahamic God that is worshipped in Christianity, and could therefore be taught in schools without contradicting the religious beliefs that American schoolchildren, in all likelihood, held in their personal lives. However, scientific developments in the 19th century brought about fierce debates surrounding the secularization of education, particularly in the natural sciences.

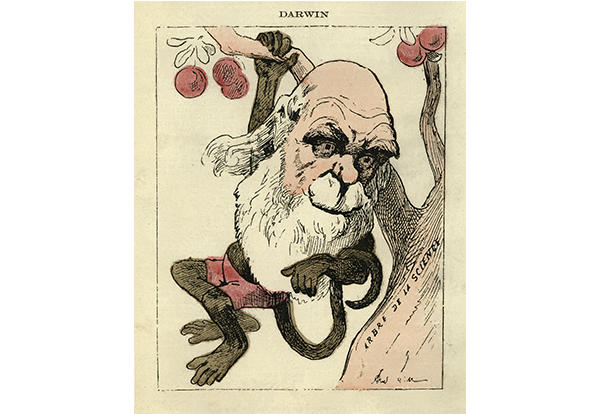

While Charles Darwin is often remembered as the “discoverer” of evolution, there were actually many thinkers from centuries prior who shared similar beliefs and observations. The first records of discussions about the permanence of species can be found from ancient Greek philosophers such Empedocles. 17th century English naturalist John Ray, known for his significant work in early taxonomy, first classified humans as primates, thus implying that humans were descended from nature. Even Charles Darwin’s own grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, believed that evolution occurred in all species, although his ideas were largely unclear. Regardless of where its ideas may have originally been drawn up, evolution never gained widespread acceptance from the scientific community up until Charles Darwin’s famous theory was published. Darwin’s theory was quite simple: all biological species, including humans, evolved over time through random genetic mutations. If a mutation was beneficial to a species’ survival, it would be more likely to be passed on to offspring, and would eventually be common through the population. If a mutation was harmful to the species, it would simply die out. While Darwin’s work was no doubt significant from a scientific perspective, its implications with respect to humans and society were also massive.

As with any new scientific idea, evolution was subject to intense criticism and debate from Darwin’s peers. So while doubt about evolution existed on intellectual grounds from many of the world’s respected thinkers, such as in the ones discussed in the famous 1860 Oxford evolution debate, the rejection of Darwin’s ideas also came as a result of adherence to religious beliefs. According to more traditional interpretations of the Bible, evolution contradicted the scripture. While the stories in the Bible had long been contradicted by a number of scientific discoveries in centuries prior, evolution had one particularly important disagreement with fundamentalist Christian belief: it claims that humans were not made intelligently in the image of God, but developed randomly over time through genetic mutations. As evolution became more widely accepted through the end of the 19th century, and interpretations of the Bible began to change, American schools began to teach theistic evolution, a version of Darwinism that was not considered to be at odds with a belief in God.

The early days of evolution being introduced in American school were surprisingly tame, with few objecting the existing harmony between science and faith that was being taught in schools. It was not until after the First World War did a rising Christian fundamentalist faction of Americans begin to assert that evolution, in any form, was directly contradictory to the scripture. By the 1920s, a decades-long series of legal and political debates about evolution and creationism in American schools began, as some states attempted to ban evolution outright in schools. Religious and social tensions, various judicial philosophies surrounding the First Amendment’s stance on religion, as well as the fact that education is a power delegated to individual states, all contributed to the complex and drawn-out nature of the issue in the United States.

One of the first major events in the debate occurred shortly after Tennessee’s ban on teaching evolution. Now known as the Scopes Trial, a Tennessee teacher was found guilty of violating this ban, although he accepted the $100 fine, as it brought national attention to the issue. A later appeal to the Supreme Court of Tennessee overturned the conviction, but only due to an unrelated technicality. The court still held that the ban on teaching evolution was permitted by the constitutions of the United States and Tennessee. This victory allowed creationists to continue their campaign to remove evolution from public school textbooks. It was not until decades later did progress in the other direction begin to occur. In 1968, the Supreme Court of the United States, under the famously progressive Warren Court, ruled in Epperson v. Arkansas that the states prohibition on teaching evolution was unconstitutional, as it was against the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The court ruled that banning evolution essentially promoted a religion on behalf of the state. Less than two decades later in 1987, Edwards v. Aguillard held that Louisiana’s law requiring creationism to be taught alongside evolution was unconstitutional for the same reason.

While any educational standards in the United States that either mandate creationism or ban evolution have long been removed, there still remains a degree of hesitation about the topic as more subtle ways to discourage the teaching of evolution have been put into place by policy makers. In 1999, for example, Kansas temporarily removed the teaching of the origin of life from its educational standard completely, leaving individual school districts to decide whether or not to teach it at all. Across several states, textbooks that contained teachings about evolution were marked with disclaimers that told the reader that its contents were not scientific fact, but were instead theory.

Though the measures taken by some jurisdictions to limit the teaching of evolution is not unconstitutional, it does represent the legacy of fundamental Christianity and religious zeal that still exists in many aspects of American society. Today, creationism continues to be taught in schools, but instead of being taught as fact, it is just one perspective that students can view in order to better understand the world around them, and to arrive at their own conclusions based on their independent reasoning.