“Myths are things which never happened, but always are.”

Salutius, 4th century CE

Every civilization in the history of the Earth has a story of who they are, and how they got there. While few of these could ever be verified by historical or archeological fact, even the most unlikely of origin stories can impact a society just as much, or even more, than if the story was certain to be true. This series will provide a brief outline of the mythical origins of a handful of civilizations, and draw historical connections between those myths and the peoples it served, or continues to serve, as a foundation to. As a whole, the series will attempt to highlight that in history, myth and fact can go hand-in-hand, and that the line between them is not always clear, nor relevant in shaping humanity.

In the beginning, there was only chaos; the world a formless disarray of nothing and everything at the same time. From the disorder emerged a dichotomy between two opposing ideas: Heaven and Earth, with the divide between the two being apparent in all worldly and spiritual things.

Japan’s creation myth is similar to others such as the Ancient Greeks or Hawaiians, who generally believe that the universe was created from chaos; that the things that made up the universe were initially or always existent, though disordered, and were then reorganized into universe we see today. Creation from chaos myths are distinct from other categories of creation myths, such as creatio ex nihlio (Latin for “creation from nothing”): the belief in a single intelligent being creating the universe from nothingness.

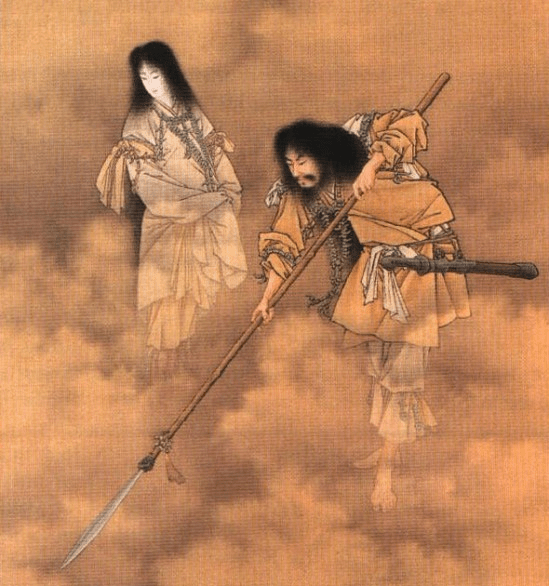

Takamagahara, the abode of the heavenly gods, was the first thing created from the chaos. Emerging from the primordial oil and now living in Takamagahara were the three original creation gods: Amenominakanushi, Takamimusubi, and Kamimusubi. Seven generations of deities were born from these original three, with the final generation consisting only of brother Izanagi and sister Izanami. The two were gifted were a sacred jeweled naginata (a traditional Japanese spear) at birth. The siblings, now standing on the bridge between Heaven and Earth, stir the sea with their naginata, creating the Earth’s first islands from the droplets that fell from the spear’s tip, and finally descending from Heaven to live on them. Before long the two realize their anatomical differences, and organize a marriage ceremony around the pillar of Heaven. Their first set of offspring are severely deformed, which they determine, after some discussion with their dead ancestors, is a result of Izanami speaking first during the ceremony instead of Izanagi. The couple redo the ceremony, this time successfully abiding by their respective roles.

The naginata, central to Japan’s creation myth, is also central to the nation’s military history. A versatile weapon—something between a sword and a lance—was used by everyone from samurai to warrior monks. Meanwhile, the pillar of Heaven, around which the wedding takes place, is replicated with the central pillars common in buildings constructed during the Yayoi period of Japan (300 BCE–300 CE). With regards to Izanagi and Izanami’s relation to each other, it is important to note that there is a level of ambiguity within certain Japanese words for “wife” and “little sister”, so scholars continue debate whether or not they can be considered related by blood. Lastly, the story about Izanami’s botched role in the ceremony reflects Japan’s traditional gender roles and historically conservative attitude towards women, as well as the Confucian philosophy on gender roles which influenced virtually all of East Asia and beyond.

The renewed union between Izanagi and Izanami results in a new set of offspring, which take multiple forms. These include new islands, geographical features such as forests and mountains, and even more gods. Finally, Izanami dies in childbirth after she gives birth to her most volatile creation, fire. A complicated saga ensues after her death, which actually results in permanent rift between couple. Izanami, now a resident of the underworld, threatens to condemn thousands of mortals to death unless her husband backs off, while Izanagi promises to do the opposite by creating an even greater number of births, thus creating the cycle of birth and death. Meanwhile, the original couple themselves aren’t the only ones having problems with each other; so are the many gods whom they created. After Susano’o, the storm god, gets into a quarrel with his sister, the sun goddess Amaterasu, the latter locks herself into a cave, plunging the world into darkness.

The new islands described as being created by Izanagi and Izanami align well with the islands of Honshu, Kyushu, and the other major islands that make up Japan. Amaterasu locking herself in the cave likely corresponds with a real life natural disaster, such as an eclipse, or perhaps the infamous year 536 CE, in which most of the world, not just Japan, experienced massive crop failure probably due to a volcanic eruption which created an ash cloud that blotted out the sun.

If all of this sounds confusing and disconnected, that’s because it is. Although Japan is considered a culturally homogenous country, that was not always the case. Its ancient peoples consisted of small independent tribes and chiefdoms, whose various myths and legends eventually culminated in an only somewhat cohesive narrative of Japanese mythology. It was not until long after these myths were created, well into the first millennium CE, that surviving records of these myths are found. The many myths that can together be considered the creation myth of Japan are a mostly a compilation of the many disputes, affairs, and fights between the gods. Many of these myths would follow a pattern such as this: a few gods get into trouble with one another, they start fighting, and something important is ultimately created as an unintended result of the fighting.

Out of the mishmash that is Japanese mythology, the two most direct and tangible legacies of the Japanese creation myth are the Shinto religion and the alleged origin of the Japanese imperial family. Shinto is considered the indigenous religion of Japan, and has existed in some form since even before the Common Era. Blending elements of Japanese folk traditions (including its mythology) and Zen Buddhism, the religion is an important symbol of Japan, influencing many of the nation’s most iconic traditions, historical events, and architecture. The semi-mythical beginning of the Japanese imperial family can also be traced to the country’s founding myths. According to legend, the aforementioned sun goddess Amaterasu—herself a descendent of Izanagi, Izanami and the original three gods—had an extensive and documented lineage of her own. Five generations below Amaterasu lies her great-great-great-grandson, Jinmu, who is considered to be the first emperor of Japan. 126 generations later, the family tree arrives at Naruhito who, although stripped of all but ceremonial powers, is the current emperor of Japan. Thus, if one were to directly trace the lineage of Naruhito as far up as the records allow, Naruhito can be considered a direct descendant of the original heavenly gods. Many readers will no doubt be familiar with fanatic acts, such as piloting a kamikaze airplane, being done in the name of Japanese emperor. These could be paralleled to acts of religious fanaticism, since both consider their actions as vindicated by the divine.

Japan is a unique nation that was formed from unique circumstances. Its mythical origin reflects the values and customs that has transformed the country from a few tribes inhabiting a handful of islands to an enduring economic and cultural power that has influenced the entire world.

One thought on “Mythical Origins Part I: Japan”