The story of eugenics in the United States and the concurrent social movements for the interests of African Americans are deeply intertwined. History has revealed that there were actually African American supporters on both sides of the eugenics argument, but usually for different reasons than their white counterparts. The relationship that black activists had with eugenics in a given time period can provide an insight into the changing goals and reasoning of the centuries-long struggle for racial justice.

As eugenics began to gain prominence in the late 19th century, some African Americans, despite the mainstream movement often labeling those of African descent as an “unfit” group, saw it as a possible way to improve their race. While some African Americans believed in protecting the racial purity of the black race (such as Marcus Garvey), or even that the black race itself was inferior (such as William Hannibal Thomas), the majority of eugenics proponents saw the ideas of “fit” and “unfit” groups as something no different from breeding cows or corn.

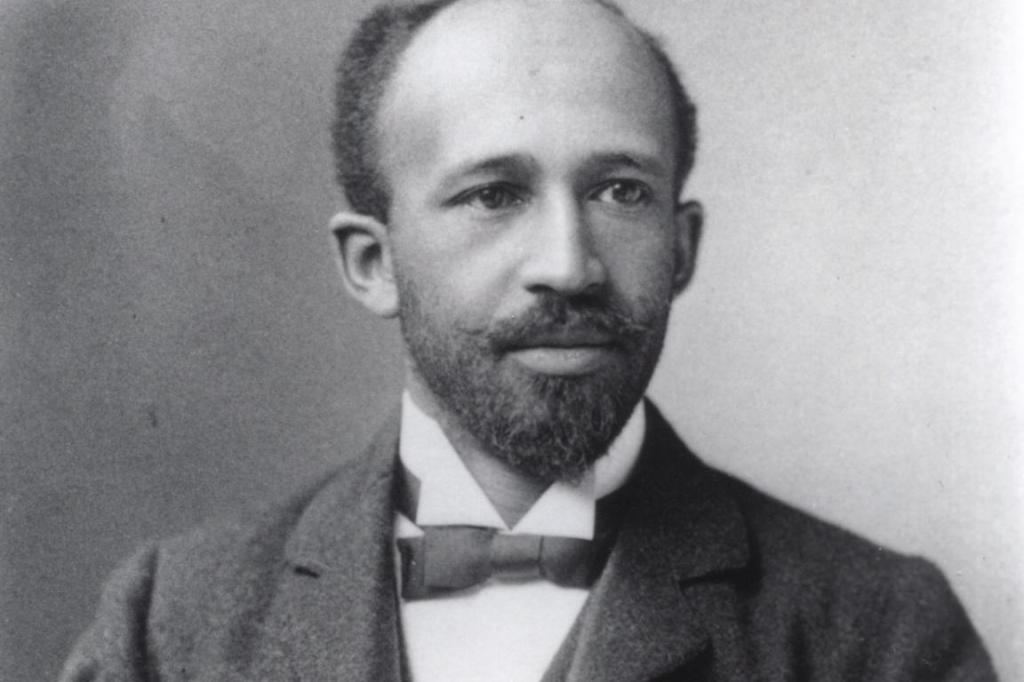

W.E.B. Du Bois was a leading intellectual within the black community, and strong advocate for “assimilationist eugenics”. He believed that it was the responsibility of the African American community to lift itself out of its current state, not just through social or environmental changes, but by selecting which of its members should procreate. Du Bois also claimed that the mixed-race children born to white slave owners (and the decedents of those children) were partially responsible for black moral decay by carrying the genes of perverted adulterers. He observed that similar to any other race, the black race contained individuals who possessed traits that were desirable or defective. One of Du Bois’ famous ideas was that of the “Talented Tenth” He believed that only the best of the race would be able to save the whole race. All the while, he insisted that the white and black races were equal, and that the differences alleged by contemporary white scientists were the result of class and environment rather than genetics.

Another prominent African American proponent of eugenics was Dr. Thomas Wyatt Turner. In contrast to Du Bois’ balanced emphasis on both nature and nurture, Turner doubled down on the ideas of biological determinism and the importance of one’s genetic background. He helped reshape the mainstream ideas of eugenics into one that better fit the notion of racial equality. Turner’s ideas were taught to thousands of black students at Howard, Tuskegee, and Hampton. In fact, a 1915 exam from Turner’s class at Howard University read, “Define Eugenics. Explain how society may be helped by applying eugenic laws“. In the end, Turner was hugely responsible for popularizing the eugenics both among the black elite, and the general African American population through his volunteer lectures. Years later, the NAACP, which Turner would help found, would hold baby contests (yes, baby contests) that were no doubt tied to the ideas that Turner helped spread.

While eugenics was viewed favorably by African Americans for decades, the emerging civil rights movement of the mid 20th century began to see the idea rapidly fall out of favor. Eugenics policies, such as the North Carolina Eugenics Board, which disproportionally affected African Americans were common in the United States, especially in the South. One policy of the generally progressive President Lyndon B. Johnson was the allocation of federal funding towards birth control in low income communities. Although the more radical, black nationalist faction of the civil rights movement already opposed the moderate reforms of the Johnson administration, this particular action sparked widespread outrage, since many saw it as limiting the black population as a way to suppress its influence in the United States.

The popularity of eugenics plummeted across racial communities by the 1950s and 60s, especially in response to atrocities of the Nazi regime, who adopted eugenics and Aryan superiority as a basis for its ideology. The fall of eugenics was particularly strong in the African American community, who sometimes highlighted the hypocrisy of fighting against injustice abroad when it was still being fought for at home. It was not long before eugenics was seen to be as conducive to black empowerment as lynchings or poll taxes were.